As discussed in the prior post, gold was a key expectation driving Queen Isabella’s conquest of “Española.” That expectation waned and resurged during the period from 1493 to 1502, affecting the desire and willingness of her Spanish ministers, financiers, and subjects to pursue and participate in the conquest.

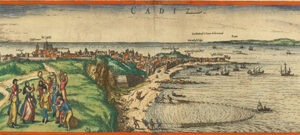

After Columbus returned from his first voyage and promised Española’s gold, he and crown ministers assembled a second voyage fleet of seventeen ships bearing 1,200 men within six months, departing Cádiz in September 1493 (depicted in Encounters Unforeseen). But when Columbus returned from the second voyage with that promise unfulfilled (1496), he struggled for almost two years to arrange resupply of Española (two ships) and his third voyage (six ships) (depicted in Columbus and Caonabó).

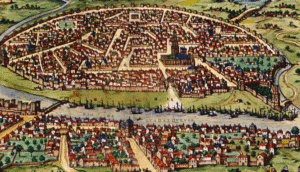

As the upcoming sequel will relate, Columbus departed on the third voyage having failed to achieve the settler recruitment envisioned, and the six ships weren’t berthed to capacity. Isabella and Ferdinand dispatched Francisco de Bobadilla to replace Columbus in 1500 before receiving non-partisan reports of the 1499 gold discovery (see prior post), and Bobadilla departed in merely two caravels. But after the gold discovery was understood in Spain, Isabella and Ferdinand dispatched Nicolás de Ovando, Bobadilla’s successor, in a fleet of thirty-two ships bearing 2,500 persons.

Over the period 1493 to 1502, fleet arranging and provisioning gradually transitioned from the coastal Andalusian ports to Seville (with ships departing down the Guadalquivir River to the ocean at Sanlúcar de Barrameda), which facilitated crown oversight. The first engraving is of the port of Cádiz, the second of Seville (both taken from Georg Braun and Frans Hogenburg, Civitates Orbis Terrarum, 1572-1617).