In March 1495, Columbus had relocated Fray Ramón Pané from Fort Magdalena to Fort Concepción to instruct Chief Guarionex in Christianity, hoping Guarionex’s conversion would serve as an example to “Indians” throughout “Española.” Guarionex was renowned for his knowledge of Taíno spirits, and he and Pané discussed both Taíno religion and Christianity for over a year—through late 1496—whereby Guarionex became a principal source for the report Pané wrote for Columbus regarding Taíno religious beliefs and practices. (For a sketch of Pané, this report, and his preaching at Magdalena, see posts of November 4 and December 1, 2022.)

Columbus had encouraged the second voyage missionaries to teach Indians the Lord’s Prayer, Hail Mary, and the Apostles’ Creed, and Columbus and Caonabó includes a scene depicting Pané teaching Guarionex the Apostles’ Creed.

In advance of Christmas, I extract my dramatization of the first lesson (Bakako is Columbus’s enslaved Taíno interpreter, known to history by his baptized name, Diego Colón):

“We call it the Apostles’ Creed,” [Pané explained]. “It summarizes everything one must understand…” He nodded toward Bakako to translate.

“Then it’s a good place to begin,” Guarionex replied courteously but doubtfully, as he expected the learning lacked comprehension of the spirits he knew. “What’s the meaning of Apostles’ Creed?”

“The apostles were twelve disciples Christ dispatched to preach God’s Word, and the creed is the Word’s core truths.”

Pané invited Guarionex inside the church, where they sat facing each other, Bakako at their side…

“Today we’ll discuss the first three truths, speaking in your language,” Pané began. “God, the Father Almighty, created heaven and earth. Jesus Christ was his only son. Christ was conceived by God’s spirit and born of the Virgin Mary.” Pané evaluated Guarionex’s reaction, perceiving him favorably moved and inclined to accept.

Guarionex was merely astonished, struck by the first belief’s wisdom of the very beginning, venturing beyond an explanation for the peoples living and the sea to encompass the sky and earth’s origin, which he’d understood existed forever—timeless, without beginning.

“Do you believe in a supreme spirit?” Pané asked, nodding to indicate he assumed Guarionex did.

“I do. My people believe that spirit is Yaya, who lives in the sky, as other spirits. Where does your God live?”

“In Heaven above,” Pané replied, pointing to the sky. “Perhaps you already believe in God by a different name?” he encouraged, eager for Guarionex to so recognize.

“What does your God look like?” Guarionex responded, instead irritated to be led.

“God created man in his image, but he is invisible.”

Guarionex was surprised by the parallel. Yaya also resembled man yet was invisible. “But your God’s son appears just as a man. So, your Christ is both spirit and man?” He observed Pané’s nod and was intrigued that a people so sophisticated believed such a combination occurred.

“That’s the essence,” Pané pronounced. “God is the almighty spirit in Heaven. His son, Christ the Lord, is also a man, and lived on earth. Men and women felt his touch.”

“Christ has pale skin?” Guarionex probed.

“People saw him,” Pané replied cautiously. “His mission on earth was for all people, including yours. Christ invites all peoples to his fold.”

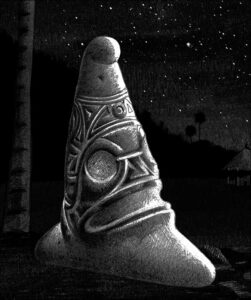

“What’s God and Christ’s relationship to the omnipotent Yúcahu?” Guarionex pushed. “Yúcahu blesses us with cazabi from the land and fish from the sea.”

“Christ is the Lord who blesses all people with bread and fish.”

“Are you saying Yúcahu doesn’t?”

“You must decide that yourself when our teaching progresses,” Pané replied, eschewing confrontation, conscious [of] the chieftain’s spirituality and intellect… [and that] Guarionex firmly possessed a religion to undue. “I assure you, all blessings and trials of men come from the Lord Christ.”

“It is Yúcahu who has provided for and protected my people since they emerged to populate the earth,” Guarionex replied softly, in dissent, yet signaling he also wished to avoid contention. He mused, taken by the confluence of similarities and contrasts. “Yúcahu is spirit, not man, and born of a woman spirit, but fatherless. Tell me of Christ’s mother.”

“The Virgin Mary is blessed, watchful for those in danger, generous to those in need, and revered among women for her womb’s fruit. She forgives sinners who repent.”

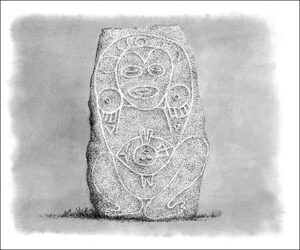

Guarionex was dumbfounded by the similarity of the Virgin’s powers to those of Attabeira, Yúcahu’s mother. “But you say the Virgin Mary is woman, not spirit. As woman, how does she award these blessings? Is she a chieftain?” He pondered whether the Virgin Mary might, in truth, be none other than Attabeira.

“The Virgin is unique, conceived free of sin,” Pané replied.

Bakako dutifully translated but grasped that Guarionex wouldn’t understand the last strange concept—that all men were sinners who needed forgiveness. He added for Guarionex’s benefit that sin would be explained in another lesson.

Guarionex and Pané discussed the first truths for an hour, amicably but with growing tension, as Guarionex gathered that Pane’s spirits ultimately would be taught as replacement to his own rather than supplementary. Pané wasn’t dismayed but grew firm that the pale men’s spirits were the true spirits, albeit flexible that parting with others wasn’t essential—until Guarionex was so convinced…

The first sketch is of Yúcahu (taken from Columbus and Caonabó), the second of Attabeira (taken from Encounters Unforeseen). The engraving of friars evangelizing in the Indies is from Philoponus, 1621, courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library, portion of rec. no. 04056-3.