Isabel, Anacaona & Columbus’s Demise depicts the origin of the system of repartimiento through which Spain would rule its American conquests, whereby Spanish settlers were awarded “Indian” lands and the Indians resident thereon as laborers.

As related in Columbus and Caonabó, when authorizing Columbus’s third voyage in 1497, Queen Isabel and King Fernando sought to incentivize their Spanish subjects to settle on “Española” permanently. They directed Columbus to enlist three hundred thirty persons on the crown payroll and authorized him to repartir—grant and distribute—hereditary and alienable land plots to these persons for building homes, farms, and vineyards so long as occupied for four years. Grants were to be awarded based on the settler’s status and service to the crown and the condition and quality of his person and lifestyle.

Francisco Roldán began a Spanish rebellion against Columbus’s rule on Española in 1497, and as narrated in Isabel, Anacaona & Columbus’s Demise, his rebels took sanctuary in Behecchio and Anacaona’s Xaraguá in the spring of 1498. Columbus’s third voyage arrived on the island in August 1498, and Columbus attempted to end the rebellion by awarding the rebels Indian slaves if the rebels departed for Spain. But Roldán and his rebels feared prosecution in Spain, and the great majority of them gradually decided to remain in Española. Settlement negotiations between Columbus and Roldán proceeded fitfully for a year.

In August 1499, Columbus sailed west to the modern Ocoa Bay, Dominican Republic (south of Azua), close to but outside Xaraguá’s then eastern boundary (i.e., in neutral territory). The photo below is of the bay, where he and Roldán met aboard ship, and by September, agreed a resolution of the rebellion favorable to Roldán. Key terms were that: Roldán and over one hundred rebels would resume submission to Columbus’s authority, provided they were granted estates of their choosing, back wages, and a pardon; Roldán would be appointed Española’s permanent chief magistrate, Columbus’s second-in-command (i.e., superior in rank to Columbus’s brother Bartolomé); and over a dozen pardoned rebels would be given a ship to return to Spain. It was understood that the land grants included the submission of the resident Indian cacique and the labor of his resident subjects, as this labor was essential to the construction of homes, farming, and the wants of the Spaniards’ daily life.

On September 28, 1499, Columbus and Roldán formalized the settlement in writing in Santo Domingo, and in October, the men agreed on the individual repartimientos awarded each of the hundred rebels. Columbus insisted that the grants be dispersed throughout island to diffuse rebel concentration in Xaraguá, which was acceptable to the rebels since many wanted to live near the gold producing area further east. Roldán insisted on retaining his own control of the lands of Behecchio—Xaraguá—expecting Behecchio’s obedience and the labor of all Xaraguáns.

Columbus then awarded his loyalists at least commensurate repartimientos. The system of repartimiento came to operate not only as the foundation for the subjugation of Native labor, but as a means by which Columbus and successor governors augmented their control of settlers by awarding favorable repartimientos to those pledging loyalty.

This organic origin of repartimiento was a far cry from that envisioned by Isabel in 1497. After she forbid enslavement of non-resisting Indians in 1500, the practices of repartimiento and encomienda would be doctrinally formalized in a manner that theoretically distinguished them from the slavery they functioned as in Española, i.e., with Indians “compensated” for their labor.

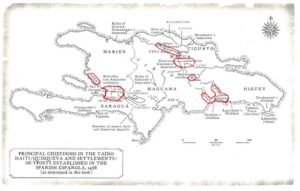

Primary sources provide partial information as to where the initial repartimientos were granted in 1499 and 1500. I have marked in red the map of Española included in Isabel, Anacaona & Columbus’s Demise to indicate roughly where many were sited.